In PART 1 of our Stefan Grossman interview, we talked a lot about acoustic guitars, what Stefan’s early instruments were like, and how his preferences evolved as the years went on. In this section, we talk about Stefan’s “European Period”, which lasted from the mid ’60s until the early ’80s, his relationship with some well-known European guitarists, and the beloved Kicking Mule record label that he cofounded with Ed Denson.

In PART 1 of our Stefan Grossman interview, we talked a lot about acoustic guitars, what Stefan’s early instruments were like, and how his preferences evolved as the years went on. In this section, we talk about Stefan’s “European Period”, which lasted from the mid ’60s until the early ’80s, his relationship with some well-known European guitarists, and the beloved Kicking Mule record label that he cofounded with Ed Denson.

W&W – When you first got to England, you had already met Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker (from Cream) back in New York… did you get involved immediately with the folk scene, or did you dabble with the rock guys as well?

Stefan – Well, I hung out with Eric… I stayed at his place, we hung out and played. The first place I went when I was allowed into England – the customs people hesitated to let me in – was to go to Gingerʼs place. He lived in a very, very modest house. We would go to a pub, Iʼd hang out with The Cream as they were getting their stuff together, I would go to gigs with them…

My friend Mark Silber had been there the year before, and so had Danny Kalb. There was a house on Somali Road… on one floor, there was a group called The Young Tradition, with Heather Wood, Royston Wood and Peter Bellamy, they sang traditional English music, unaccompanied. On the other floor was John Renbourn and Bert Jansch. I just went down to say hello to The Young Tradition, I didnʼt know them… they said “Weʼve heard all about you, play a set at this club…” I had my Stella, and I did a set. Somehow, there was a reporter from The Observer, and I was written up in the Sunday paper! Heather said “You know, you could play around here, thereʼs folk clubs, thereʼs a whole scene…”

From Heather I met John and I met Bert, because everyone was playing at a club called Les Cousins… Roy Harper, John Martyn, Al Stewart, just all hanging together… I think it was Martin Carthy who took me over to meet Davy Graham. I would meet these guys at the clubs, and I would tour with them. Bert and John were just getting The Pentangle together, so they had me open up some Sundays at their club at The Horseshoe. So people start to get to know you, and I became good friends with people. I became close with John, with Bert…

W&W – Pretty much all the seminal British players say that Davy Graham was ground zero…

Stefan – Iʼve never understood that.

W&W – What was your initial impression of him?

Stefan – By the time I got to know Davy, he was past that. Eventually, when we started Kicking Mule, we sort of resurrected Davy, and he started to play stuff that was interesting. But in America I was used to David Laibman, he had just come back from England. He had also played with Bert and Davy, and he spoke very highly of them… but in America, we were playing some complex stuff!

So I go over to England, and what impressed me wasnʼt the people playing blues… I thought [Stefan makes a “grossed-out” noise, like a kid who doesnʼt like the look of his creamed corn…] I felt like they were missing something. When they were playing guitar instrumentals, it sounded like cheap Chet Atkins stuff. What impressed me was Bert and Martin. When they were playing their British stuff, they were able to create a very unique style to accompany British traditional music. It wasnʼt based on boom-chick, and it wasnʼt Mississippi John Hurt playing “She Moved Thro The Fair”… but they all spoke incredibly highly of Davy.

I would hang out with Davy, and his brain cells had been somewhat compromised by too much heroin… but he was off it, he was clean, but he was still a peculiar character… but really nice, really friendly. But I just didnʼt see that brilliance. To me, a David Laibman was Earth-shattering, maybe not the sound that heʼs producing, but his approach to the guitar… but they all spoke of Davy like that was it, and of “Anji” as this incredible tune, and they audience would go wild over “Anji”… to me, it sounded like a watered down version of “Windy and Warm”, that we would play in America. That was a much more interesting instrumental than “Anji”. But I donʼt know, they still stick by their stories! There are now recordings of Davy in his early years, before the Decca records came out, and I still donʼt hear that “something special”.

W&W – What about the exotica, that side of it? Did you recognize that as something important?

Stefan – No, no! Because we had Sandy Bull here!

W&W – Were Sandy and Davy developing independent of each other? I make that connection as well, but did the British guys know about him?

Stefan – They may have known about him, because of the records… but I was hanging out with John Fahey, and while John wasnʼt exotic, Robbie Basho was! He was doing some heavyweight Eastern music, and heʼs never really been recognized… because he would sing, and he had this operatic voice… but he was incredibly creative. So comparing [Davy] to Basho, Sandy Bull, they were influenced by the Indian music… and Davy was doing stuff like it, but it was not of a higher caliber, thatʼs for sure. So no, it didnʼt impress me. Not at all.

W&W (huge Davy Graham fan) – Okay, okay…

Stefan – [sarcastically] That will make me friends! Do you feel the same way, are you trying to figure out what it was [all the fuss]?

W&W – I actually love his playing! I love the mercurial element of it, the way he tackled the fretboard… if I had known him, maybe it would have been different, I donʼt know… I might have thought him strange or aloof… but from that group of British players, I thought he had a very unique feel. He was also one of the first players that I really got into, along with Bert.

Stefan – Well, the scene in England was actually a little stagnant. When I came along, basically playing Laibman arrangements and lots of blues stuff, I wouldnʼt present it as a blues singer… Iʼd present it as a guitar player. That, I think, is one of the reasons that I got accepted in England. I was saying “Hereʼs this stuff, I learned this from Skip James, I learned this from Reverend Gary Davis…” I was sort of a bridge, and they liked that. I wasnʼt a “personality”. I think that sparked something there, and there was this little bubble.

But over the years, since the late ʻ60s, itʼs John Renbourn whoʼs constantly developing. Constantly exploring new territories. Heʼs not recording enough records, so the people out there donʼt all realize what heʼs doing, heʼs doing a lot of composition at home. He was constantly growing and growing, whereas Bert did his brilliant stuff early in his career. Martin Carthy got a brilliant thing and he stayed with it, itʼs always great!

W&W – Love him!

Stefan – But John Renbourn kept growing, doing arrangements of medieval tunes, of jazz tunes, of whatever. We hung out for fifteen years, touring the world, and our conversations were constantly about guitar playing. He was very interested in parlor guitar, he did his thesis for university on that. We would talk about American guitar styles, how it affected the English, etc.

W&W – Were you initially unimpressed by Renbourn? He was doing lots of straight blues…

Stefan – Well, I was unimpressed, because remember Iʼm hanging out with Eric! Clapton was a great blues guitar player, with incredible tone… Iʼm talking about when Eric is playing acoustic, which at that point people werenʼt hearing. If you were just playing together, you would see Ericʼs hands, and the vibrato, the tone, the phrasing…

W&W – Did Clapton already have some Robert Johnson arrangements under his belt?

Stefan – No, he didnʼt, but he had a complete vocabulary, just as big as my vocabulary was, of pre-war and post-war blues. He was obviously better with the post-war, he was

taking, letʼs say, Tommy McClennan and putting it on the electric guitar. He listened a lot. He was really involved in the music, trying to hear as much as he could.

W&W – He got Skip James songs onto Cream records!

Stefan – Yes!

W&W – So you hurt your hand at one point, and you became a singer/songwriter.

Stefan – Yes… well for one thing, because everyone was doing singer/songwriter stuff, all my friends… Al Stewart, John Martyn, Roy Harper… and what happened was that I was living in Rome and went to a furniture store, and it had a real modern door. It was a metal door, and the jamb was very close to the handle. So as I was leaving, I closed the door and my thumb got caught it the jam. It literally amputated my nail, all the way to the bottom, so it hurt too much to fingerpick… but I could bandage it and hold a flat pick. So I just started, for it must have been six months, just writing songs and strumming. It was interesting [to me] because the record company wanted to do songs.

W&W – Was this Fontana still, or Transatlantic?

Stefan – No, Transatlantic. So I had done a record called Ragtime Cowboy Jew, which was a combination of songs and instrumentals. That sold well, but the next one was just singing and playing guitar, with guys from the Cat Stevens band, some friends I had that were more in the pop world. That really got slammed! The critics, they wanted me to shut my mouth and just play guitar!

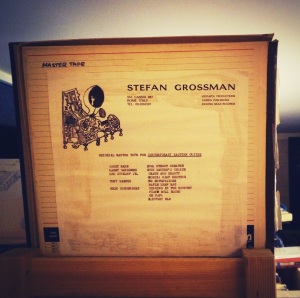

We did another one, Hot Dogs, which was kind of going back to my roots, I guess… and I did Yazoo Basin Boogie, which was recorded in a closet, when I was living in Rome. I put blankets around it, and I sit in this little closet with a Tandberg mono tape machine, and I would play instrumentals. I recorded that, and they put it out, and it was a really big hit! But to show you how crazy reviews can be, I remember the Rolling Stone magazine saying it was the best recording of an acoustic guitar, and it was just mono in a closet! Give me a break!

W&W – So during your singer/songwriter period, where did your lyrical inspiration come from? Were they really sincere, or just keeping with the lyrical poetics of the times?

Stefan – No, really sincere! I would use a lot of biblical references. I was a young twenty year old…

W&W – Did Paul Simon loom large on the British scene when you first got there?

Around that time, I remember going to Colletʼs Record Shop, where everyone used to hang out. I was friends with a guy who worked at Colletʼs, Hans Fried, who one day told me that Paul Simon was trying to get a hold of me. I thought, “Paul Simon… whoʼs Paul Simon? Pop star..” But for months, wherever I went, people would say “Paulʼs trying to get in touch with you” and I thought “Who cares?” But finally, it must have been November, I was staying with a friend who was a writer for The Guardian and The Observer, and he was there when I called up Paul. It turned out that Paul had a bulletin board with all my clippings… he had them, I didnʼt have them! He was splitting up with Art Garfunkel. So I said that I would be coming over [back to the US] around Christmas time to see my parents, and we would get together.

So we got together, and at that point he wanted to change, to go solo. For that next year, I would be with Paul. I would be over in Europe and I would get telegrams asking if I could catch a flight to go over to Columbia Studio E in New York, or L.A. or San Francisco… all these great studios, incredible musicians. At the end of the day, I ended up just being on one track on that first Columbia solo record.

One of the funny stories was when we went down to Nashville, we went to the Quonset Hut [studio]. Each one of these studios had a specific sound, and Paul, it was quite amazing… he would get the best musicians possible, in the most unique studios that had a sound and a history… so we went down there, and I had brought the Dikeman guitar, the [Martin] 000-45. The players came in, and the drummer, Kenny Buttrey, came in and his eyes were all bloodshot because he had been up for 24 hours, doing session after session. So Paul said we would take a break, come back in six hours.

One of the funny stories was when we went down to Nashville, we went to the Quonset Hut [studio]. Each one of these studios had a specific sound, and Paul, it was quite amazing… he would get the best musicians possible, in the most unique studios that had a sound and a history… so we went down there, and I had brought the Dikeman guitar, the [Martin] 000-45. The players came in, and the drummer, Kenny Buttrey, came in and his eyes were all bloodshot because he had been up for 24 hours, doing session after session. So Paul said we would take a break, come back in six hours.

So I was talking to the musicians, showing them the guitar, and these are working musicians, so to them it was just a piece of bling. So I went to George Gruhnʼs shop to trade the guitar, and I came back later on that evening with twelve instruments! That 000 was a real collectors item, so I traded it and came back with a sunburst OM-28, a Les Paul sunburst, which I later sold for nothing, banjos, tons of instruments… I thought, “How funny this is, this New York guy leaves with one guitar and comes back with all this stuff, like a carpetbagger…”

But it was very interesting working with Paul. He was a very generous, wonderful, smart person. What he does with musician is also interesting… he would get top-flight musicians, the best studio musicians there are. The musicianʼs idea is to go in there, do two or three takes, youʼve got it, youʼre happy, thank you very much… itʼs usually a good vibe, telling jokes or whatever… but Paul would say “Can you do another take? Can you do another take?” until the musician is out of ideas, out of the natural, knee-jerk stuff. Paul would do that until something really unique comes out. So when you listen to the record, the sounds that Paul is getting out of those musicians, you almost donʼt see it coming, theyʼre digging so deep into their psyche. When Paul was in England trying to record “America” with the Cat Stevens band, they were recording for two weeks and werenʼt getting anything, and the guys didnʼt understand it, they felt like they had failed! But they just had to get on Paulʼs trip, to keep playing until something was flowing that youʼve never done before.

W&W – Paul Simon was also a sonic architect in the studio, cutting takes together…

Stefan – Well, and Roy Halee, he was an incredible producer. Iʼve been in the studio

and seen Roy Halee get sounds out of instruments, I just couldnʼt believe. That whole team that works with Paul is great.

W&W – Iʼd love to talk about Kicking Mule.

Stefan – With Transatlantic, that was run by Nat Joseph, a Jewish guy from London. He and his wife were trying to have children. Initially, I licensed Yazoo Basin Boogie to him. Well Iʼm a Brooklyn Jew, and I would also go there with my newborn son David, to negotiate contracts. I realized that was a good thing to do, because it would loosen up Nat… Nat had a reputation for being a real son of a bitch when it came to contracts. But for me, I licensed [the album]. After that, he signed me for three or four records, but always licensed, so that after seven years I owned them, the records would come back to me.

W&W – Whereas usually, the artists werenʼt thinking that way, they just wanted a record company to back them up long enough that they could have a go at it…

Stefan – Right. Guys like Bert Jansch, Ralph McTell, they couldnʼt believe that that was the deal I was getting, you know? But who knows exactly why, was it because I brought my son there, or we were landsmen? Who knows, maybe that meant something to Nat.

At that point, I had these masters. I didnʼt go to Europe to become a professional musician, but at that point I was a professional, so I thought, “How can I get these released in America?” So I wrote to John Fahey, who was a friend, asking if he would put the records out on Takoma, and he never got back to me! Never wrote back…

When John put together Takoma records, he put it together with Ed Denson, who was a very good friend [of mine]. I used to stay with him at his house in Berkeley, or he would leave, the house would be empty and he would give it to me. So at that time, Ed had already been booted out of Takoma, and I said “Why donʼt we start a record company?” At that point, he had been the manager of Country Joe & The Fish, and they had gotten very popular, but I think they had broken up. He liked the idea of the label, so I went over and told him that I had all these masters, plus I knew all of these guitar players who were not professional, necessarily… Ton Van Bergeyk, Leo Wijnkamp, Peter Finger, really good kids that Iʼm seeing… I say kids, I was maybe five years older than them…

But out of Holland, I mean, Ton was fantastic! He introduced me to Leo and he was fantastic, along with Ton Engels. So I said [to Ed] that we could do records, but letʼs make them different, letʼs put tablature books in them, the way Elektra had with How To Play Blues Guitar.

The name Kicking Mule came about because Ed was a stamp collector. He would collect one commemorative series, and keep on collecting it, and as a result he would find tons of variations on these stamps. One of the famous postmarks was of a kicking mule, so thatʼs how we got the name.

I was also friends with a company in Sweden called Sonnet Records, and Sonnet decided to open up a London office. I went to Rod Buckle, who was their English representative, and asked him if he would put out our records there. So it was different from Takoma, which was a small American company, in that we had US and European distribution.

W&W – You guys were a true transatlantic label.

Stefan – So we were able to put out records that would be released in both territories, and they would eventually be licensed to Australia, etc… and the idea of the tab booklets made them really different. A lot of people signed on, and in America there were some records of, say, Ralph McTell or John Renbourn that hadnʼt been licensed, and we were able to license them there. It grew very nicely.

Ed eventually moved to northern California from Berkeley, to some kind of a farm… and unbeknownst to me, after a while he forgot to send out royalty checks! Itʼs one thing not to send out checks, but you at least have to send out statements, so artists know what theyʼre owed. Artists always think they sell five million records, when they may have sold five! But they need to know what theyʼve sold! When I found that out I said “You canʼt do that, I have a reputation, blah blah blah…”

So we decided to end it. What happened was that I decided to take all of the records that I produced, which was all the guitar stuff – Ed had gotten very involved in producing dulcimer records, banjo records – he took all that stuff, which he subsequently sold to Fantasy Records, which had also bought Takoma Records. So I had my 45 or 50 masters of all these guitar players, and they lay dormant for a long time. So now these last four or five years, Iʼve decided to reissue this stuff. But now, itʼs a pain in the ass to make TAB booklets, to print them up, because you have to decide how many to do, the paperwork…

W&W – Well, I had a question about that… was there a point, even back in the LP age, where that was becoming untenable? The costs and such?

Stefan – No, you were always able to do it. Sometimes it was handwritten or somehow funky, but people didnʼt care, they just want tablature. In Europe, they were printed and put into the LPs, whereas in America, I think you got a card and people had to send for it, and get a spiral-bound 8 1/2 x 11.

So at a certain point with the Guitar Workshop [Stefanʼs current company that produces CDs and DVDs] here, I decided that it was the right time… even though the CD world

has collapsed completely, as far as the market, I think itʼs important historically to have this stuff available. Now weʼve had the TAB booklets redone more professionally, and we include it on the CD as a PDF file. Just about everything has been released now. Some donʼt sell at all, but some sell a lot. The way Guitar Workshop functions, itʼs very important for me to do things for posterity, for historical reasons. The things that sell underwrite the things that donʼt sell. We donʼt look at the “bottom line” type of thing.

W&W – What was the scope of the LP releases back in the Kicking Mule days? How many were pressed?

Stefan – Five to ten thousand, usually.

W&W – I was curious to get a handle on just how rare they are… sometimes youʼll be able to pick one up in a record shop for $5, sometimes theyʼre on Ebay for $50.

Stefan – Well itʼs also different pressings. The European pressings were much better, the quality of the vinyl. Plus, the European tracks that I produced, I would use Malcolm Davis to cut the masters. Malcolm was the one who did all The Beatles records at EMI. Itʼs was much easier to work in England because itʼs such a little community, everyone knew everybody… at least in those days. So the quality we were able to put in was pretty good. But the quality of the vinyl was much better in England than it was in America.

W&W – Good to know! Please talk about producing those records… some were recorded in kitchens, some were recorded in studios…

Stefan – Yes, some were just done on a simple Tandberg or a Revox.. with Ton Van Bergeykʼs first record, I was becoming very good at splicing tape, editing… Eventually, I began recording at Livingston Studios, and Nic Kinsey was a fantastic engineer, though heʼs passed away now… so after maybe the first ten records, the recording quality is better.

…though certain big sellers, Country Blues Guitar [with Rory Block] half that record was done on a mono Nagra machine, and Tonʼs Famous Ragtime Guitar Solos was all done on the Revox.

W&W – Was your perspective that with someone like Ton Van Bergeyk or Lasse Johansen, these sort of guitar-monster European players, that the playing and the arrangements would speak for themselves, and that you didnʼt have to fuss so much over the sound of the recordings?

Stefan – No, we tried to get the best sound possible, always. In the studio, the problem was that the guys who played the real intricate arrangements, they could never play them from beginning to end, so you needed to have a good editor, whether it was me or Nick, who could cut it up and put it together. So the sound quality was very important, but since the music had such strong melodic content, it wasnʼt as important as quote-

unquote “New Age”, Windham Hill types of things that were more…

W&W – Atmospheric.

Stefan – Yes, atmospheric. As for me, I wasnʼt into the atmospheric stuff, I thought that quite a bit of it was just open tunings gone ape-shit! There were some players that were doing good things, Alex DeGrassi is great… the initial stuff that [Michael] Hedges did with the tapping was interesting, though in the rock and roll field, they were tapping all the time!

W&W – It just seemed more novel to do it on acoustic guitar.

Stefan – Yes, more novel. But when he would do fingerpicking stuff, I was not impressed at all. Ariel Boundaries I liked, I liked the sound of that, it was good atmosphere and I could dig it… but he did an instrumental dedicated to Pierre Bensusan and I thought, you know, “Give me a break!” I was working with Dave Evans, and Dave was doing original instrumentals, but they were so much stronger than anything that was coming out of the other part of the world.

W&W – Dave Evans is a huge hero to my generation of players! He really appeals to almost everybody, and I think a big part of it is that performance from The Old Grey Whistle Test [Evans performed his signature “Stagefright” on the show in the ʻ70s]… heʼs like the coolest guy that ever lived, just playing effortlessly! I know a writer in the UK who would love to interview him, is he still reachable?

Stefan – Oh yes! Dave lives in Belgium. He was a merchant seaman, and he started to play guitar late in life, after his 20s. He was basically a singer/songwriter, but as he was doing that, every once in a while some nice instrumentals would pop up. At one point I approached him, because I had been gigging with him as well, and I said “Dave, Iʼd love to do a record of your instrumentals.”

W&W – And that became Sad Pig Dance, right?

Stefan – Right. I didnʼt think we [Kicking Mule] could represent him as a singer/ songwriter, because we werenʼt like a Warner Brothers, you know? So we were able to get a very high quality studio at night, midnight to 5:30 in the morning, and those were all first takes, second takes, very little editing…

After that, he really wanted to do the singer/songwriter thing, so I said that we could do some demos, and I could help him shop them around… but noone was interested. So we made the record, and it was called Take A Bite Out Of Life, and that album has a couple of instrumentals… but we really didnʼt have the facilities to market it. You had to have a PR guy, come out with a single, all this stuff… but every time that he would come into town, I would tell him if we were making an Irish record or something, and we would record four or five tracks, instrumentals, and weʼd put them on these anthologies.

Eventually, he just left playing, got more involved in pottery, and moved to Belgium.

W&W – But were his singer/songwriter records at least embraced by the Kicking Mule fan base?

Stefan – No, because heʼs not a great singer. His instrumentals are great, and his songs are great, but heʼs not a great singer.

W&W – His lyrics were kind of fluffy, too.

Stefan – A little bit “flower power”, yeah!

W&W – Were the artists in the Kicking Mule stable matching your energy? Were they touring and promoting to help make the albums successful?

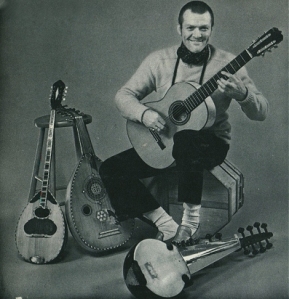

Stefan – What we did in England was that I was already performing a ton, so we would do Kicking Mule tours. We would have me, Marcel Dadi, Dale Miller, Leo Wijnkamp… basically, I could do the gig by myself and get payed x amount of money, the promoters didnʼt know the other people… but I would say that we [all of us] should just do it, and share the money evenly.

We would do tours all over Europe. One time we did a tour and it was myself, Happy Traum, Art Rosenbaum and Duck Baker… and in those years there was a lot of terrorism, terrorist attacks. As we entered France, we were stopped by the police, and I was driving. The police asked for everyoneʼs passports, so everyone handed over their passports… so the policeman asked me “Whoʼs in your car?” and I said “Duck Baker, Art Rosenbaum and Happy Traum.” He looks at the passports and says “Come with me.” So I went into the office, and he asked again “Whatʼs the names?”

After about a half an hour, I went back to the car, saying “Duck Richard Royal Baker the Fourth! Harry Traum! Art Sparks Rosenbaum!!” I hadnʼt known their real names!

W&W – All this time everyone was just getting by on their “blues” names!

Stefan – But in Europe it really worked well, we were touring, promoting the records… Ton Van Bergeyk didnʼt like to tour, because he was very nervous. In fact, on Tonʼs records, the playing is so incredible… but also accessible. The arrangements were made that way. But eventually you thought that he could do it, that he would get a nervous breakdown trying to perform the stuff… so he eventually ended up playing rhythm guitar, Eddie Lang-style guitar and harmonica in the Dutch jazz bands.

W&W – Iʼve seen some of those clips. He also puts up some great ukelele solos, things like that.

Stefan – Heʼs a great musician!

W&W – Did you ever having a feeling while you were in Europe, that you were losing touch with the blues, or missing anything that might be going on back in the states?

Stefan – No, I was coming back all the time. By the time I had left in ʼ67, most of the blues players, John Hurt, Skip James, Bukka White, theyʼd already been rediscovered. Quite a few of them were starting to pass away, Reverend Davis passed away in ʼ72… the people that were coming after that werenʼt as important or as vibrant, and the music they were playing wasnʼt as intense or as interesting, and I was never that interested in things like Chicago blues. I was interested in the acoustic guitar, and how unique it was in the blues tradition, and all these different sounds that were developing… whereas when you start to listen to electric guitar, it starts to get a little bit same-y after a while.

Pingback: Stefan Grossman, The Work & Worry Interview – PART 3 | WORK & WORRY

Davy Graham…..so highly regarded in part because-apart from Steve Benbow- he was the very first. In ’50s London the only guitarists around were Jazzers with some classical.Few people had any knowledge of blues music or how to play it,or guitar playing in general. have a clear memory of an older Irish folkie describing most 60s folk guitar playing as ‘five fellas bashing away on the chord of D for 15 minutes’.Even Martin Carthy says that most people simply did not know what they were doing!

In conversation with Derek Brimstone I was told,’Bert got it from Davy’s sister,John heard Davy,Martin Carthy looked up to / referenced him and so on,but WHO did Davy get it all from? Part of the answer is that when Big Bill Broonzy came across to Europe he did some street busking as well as paid gigs and in London his ‘bottler'(person who guards the money/shakes the tin) was none other than a teenage Davy Graham! From the days he first started gigging around London(including a stint with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers to 1963 when he first got involved with heroin Davy was apparently miles ahead of everyone else-by their own admission.Grossman got to the UK sometime after Davy had ‘gone to sleep’ and most of the best stuff was probably never recorded-never mind re-issues.Perhaps you really did have to be there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Benbow

Dave Evans….for a little extra taste of what he was all about,try these wonderful lo-fi performances done in Bristol sometime in the 90s.The self made guitar seems to have been retired-this one’s made by John Le Voi but the music’s strong,very much how I remember him playing in British folk clubs.

To find the rest,go to you tube and type in Dave Evans Bristol Ron.I think there are about eight more,including another airing of Stagefright.