Chuck Johnson is based in Oakland, CA. In addition to writing scores for film and dance, Chuck has worked extensively in the fields of modern composition and experimental rock, and also composes very fine acoustic guitar instrumentals. We recently interviewed Chuck about his appearance on the new Tompkin’s Square compilation Beyond Berkeley Guitar, which features new music from seven Bay Area guitarists. Chuck’s track is available as a free download at the link above.

W&W : Please describe the guitar you play on your track, how long you’ve owned it, where you got it.

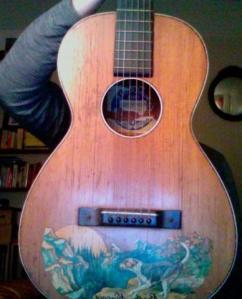

It’s a 2001 Martin 000-17s. I bought it new in ’01 or ’02 from Elderly, after playing one at a local store (I lived in North Carolina at the time.) The 000-17s is an all mahogany guitar with the older Martin 000 design – 12-fret body, slotted headstock, longer scale and wider neck. It is really fun to play and has a melancholy voice that works well on certain pieces, especially in the open D tunings. Martin ended up only making a couple hundred of them for some reason, and I have played the 000-15s that looks identical and is still available, but it has different bracing and just doesn’t have the same mojo in my opinion. Like any mahogany top guitar it takes a little more work to get the top moving, but I love how the mid-high overtones sing out when you drive it, kind of a lower register than what you might expect from a spruce top.

W&W : What is the tuning / capo position (if any) on your track?

D A D F A D (open D minor) with a capo at the 2nd fret.

W&W : How do you know Sean Smith? How did you get involved in Beyond Berkeley Guitar?

When I finished my MFA in Electronic Music at Mills College last year and started paying solo guitar shows people started telling me I should meet this guy Sean Smith and check out his music. The two people who told Sean the same thing about me were Trevor Healy and KC Bull. Trevor is a luthier and a great guitarist who is also on the comp. I initially met Trevor through a mutual friend from the Mills and Bay Area improvised music world, and he discovered that I play fingerstyle when he did some work on one of my guitars last Fall. He told me about Sean and the compilation and he suggested that Sean include me on the record. KC Bull saw me play a solo guitar show back in September and asked me if I would play for one of the screenings of the excellent documentary she made about her father, Sandy Bull. KC also mentioned me to Sean and within a month or so Sean got in touch with me about being on the comp. It was only after we had been talking for a while that he realized that I was in Idyll Swords and that he had heard my music before.

W&W : Please describe the recording of your track. Home? Studio? Home studio?

The track was recorded by my friend and brilliant engineer The Norman Conquest at Ex’pression College for Digital Arts. Norman works at Ex’pression and has access to their studios and high-end gear. He has been helping me with the slow process of documenting my solo guitar work since October of 2009. I have been composing and playing fingerstyle for a long time but until recently it has taken a back seat to collaborations and other projects in terms of trying to get the music out into the world. It is kind of ironic considering that I just finished a graduate program in electronic music, but I decided last year that it was time to focus on getting some good recordings of acoustic guitar, and Norman has been very generous and helpful with that. We recorded in Norman’s favorite room at Ex’pression, known as the Heptagon.

W&W : The words “American Primitive” are thrown around a lot these days in reference to modern acoustic guitar music. What, if anything, does “American Primitive” mean to you?

The aspects of that term that I relate to suggest a practice of making music that liberates the guitar from an accompaniment role, with a decidedly American attitude of making the rules up as you go. That is, acoustic steel string guitar as a solo instrument, compositional palette, and a vehicle for personal expression for a self-taught and intellectually curious musician, creating a vernacular derived mostly from North American folk sources but combined freely and perhaps somewhat naively with elements and techniques from other guitar dialects such as classical, flamenco, Brazilian, etc, as well as with modal Eastern forms. And with a very open-ended approach to composition. This was a radical idea when Fahey and his colleagues began putting it into practice, especially in the context of a purist folk revival scene that was very concerned with ideas of authenticity and tradition.

W&W : Please discuss ways that you go about constructing a guitar instrumental, or alternately, what do you think makes a great guitar instrumental?

I wouldn’t say that I have a process that applies to every piece. It usually starts pretty intuitively and out of improvisation, sometimes while playing another tune. I definitely latched onto something Derek Bailey said in his book Improvisation – that all music starts as improvisation, no matter how methodical the composition process. In a way, my piece on the compilation was written using a process that is more systematic than I typically use. I wrote “A struggle, not a thought” specifically for the comp, and I wanted to make a piece that was short and didn’t have as much repetition as my guitar tunes usually have. And I wanted it to have a syncopated theme that varies at the beginning, and then drops out into these sparse minor voicings that are actually built using the “tintinnabulism” technique developed by composer Arvo Pärt. So it was almost like an exercise or a puzzle. I got pretty deep into Pärt’s harmony system when I was in grad school, but it hadn’t occurred to me to try and use it on a solo guitar piece. After the piece was finished and recorded, I noticed that the structure suggested a certain narrative – the way the theme starts, then stops, then changes at the beginning makes me think of trying something over and over that just doesn’t quite work, like running into a wall. And only when the theme is abandoned and a completely different approach is taken does the piece move forward.

As for what makes a good piece… I have been discussing this same issue with Rich Osborn, who I recently began to study with (a big deal for me because I never really had a guitar mentor.) Something Rich and I agree on is the importance of a narrative, and the way a good piece changes shape and moves through a landscape. I personally believe that a good piece has to have a certain pathos – not necessarily a melancholy feeling, but rather like what German cultural theorist Aby Warburg meant by pathosformel or “pathos formula,” an emotional gesture that communicates something engraved in our cultural memory. I think this is also related to the idea of duende that is referred to in flamenco culture. When I think of my experience hearing great guitar pieces or performances, like the first time I heard an Elizabeth Cotten recording or when I saw Hamza El Din perform, it’s like the experience of someone or something reaching inside of my chest, grabbing my heart, and just slightly rotating or shifting it and leaving it that way, so that I am changed by the experience, and future experiences will be perceived through this altered perspective.

W&W : Do you see parallels in your approaches to avant-garde music and solo guitar music?

Well this relates to the “American Primitive” discussion. Because I would say that I am equally influenced by a similarly iconoclastic and autonomous stream that developed around the same time in the field of classical music among the so-called “American Experimentalists,” in which composers began working outside of the hallowed institutions of High Art, performing their own music, inventing their own instruments and notation systems, exploring acoustic phenomena, working with radically new forms (in many cases informed by Eastern traditions) and basically pissing a lot of people off. I do make abstract, noisy electronic music and sound art, and I compose music in a minimalist vein, but I don’t really consider it “avant-garde” since I am mostly engaged with ideas and technologies that have been around since the 60’s and 70’s. In a field that is largely concerned with appropriating the newest technologies and writing software to make computers more sentient, most of my experimental music is actually pretty old-fashioned.

I have only recently begun to see how my experimental work and guitar music are parts of a larger whole. For years I was actually pretty self-conscious about having such a compartmentalized approach, and I envy people who have their one thing that they do and that is what they are known for. But I would say that with the guitar music as well as the pure sound/experimental work, I am always concerned with that thing that is happening apart from the “music” – the way the sound fills the space, the overtones, difference tones, feedback, unexpected or uncontrolled phenomena, and the internal experiences of the performer and listener.  Lately I am obsessed with this little beat up parlor guitar from the 30’s. It has that light ladder bracing that just makes it a different instrument, in my opinion. Like something between a guitar and a banjo. The more modern X-bracing was invented to control the overtones and have a more pronounced fundamental resonating from the wood – to stabilize the wood, essentially. But with an old guitar with the ladder bracing you can hear so much crazy stuff happening when you strike a note – overtones, wolf tones – it’s less stable or controllable, and magic stuff can happen when you play fast and get all those sounds ringing out at once.

Lately I am obsessed with this little beat up parlor guitar from the 30’s. It has that light ladder bracing that just makes it a different instrument, in my opinion. Like something between a guitar and a banjo. The more modern X-bracing was invented to control the overtones and have a more pronounced fundamental resonating from the wood – to stabilize the wood, essentially. But with an old guitar with the ladder bracing you can hear so much crazy stuff happening when you strike a note – overtones, wolf tones – it’s less stable or controllable, and magic stuff can happen when you play fast and get all those sounds ringing out at once.

W&W : Your track on BBG has a distinct room ambience that sets it apart from the rest of the collection… do you spend much time chasing the right guitar sound on your recordings, or do you have “go to” mics and mic-placements that you typically use?

I ended up using quite a bit of the room mics when I mixed the track. The Heptagon at Ex’pression is just an amazing sounding room – not a huge reverb, but very balanced and open sounding with wood floors, high ceilings, and the unusual dimensions that give the room its name. I think the close-miked sound that is popular in a lot of contemporary fingerstyle recordings can be very beautiful and can compliment technical playing. And I might have leaned more towards the close mics on a different piece. But for “A struggle, not a thought” I wanted to hear those minor voicings ring out and decay with quite a bit of ambience, to create a sense of distance. I love how an acoustic guitar can simultaneously sound intimate while filling the room and making overtones swim around in the air. And when you listen to someone play a guitar you aren’t listening with your ear a few inches away from it.

I have tried different mic techniques over the years. In the right room, a mid-side stereo setup can be really nice. For this session, Norman had a cool idea – he put an Earthworks cardioid in the usual spot where the neck meets the body, but then he put a large diaphragm condenser behind the guitar pointed at the endpin. This brought out some nice low-mids and complimented the sound of the Martin. With a nice stereo pair in the room, of course.

Buy Beyond Berkeley Guitar from Tompkins Square

Buy Beyond Berkeley Guitar from Insound

Great interview. Just ordered the new CD. Love new and creative guitar sounds. These guys are good.

Great article. Chuck is a great guitarist, composer, improviser, and cares deeply about art and how he can further advance the musical form. Cheers again Chuck, and I hope to see you soon brother.

Ben

Fantastic description of American Primitive! That has to be one of the most well thought out and well articulated portrayals of what this style is all about.

-Scott

Pingback: Live Tracks – Chuck Johnson @ the Ivy Room

Pingback: New Digital Album : Chuck Johnson “A Struggle, Not A Thought”